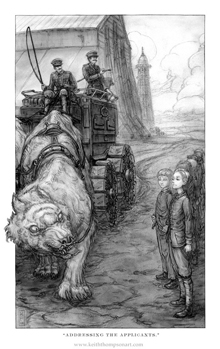

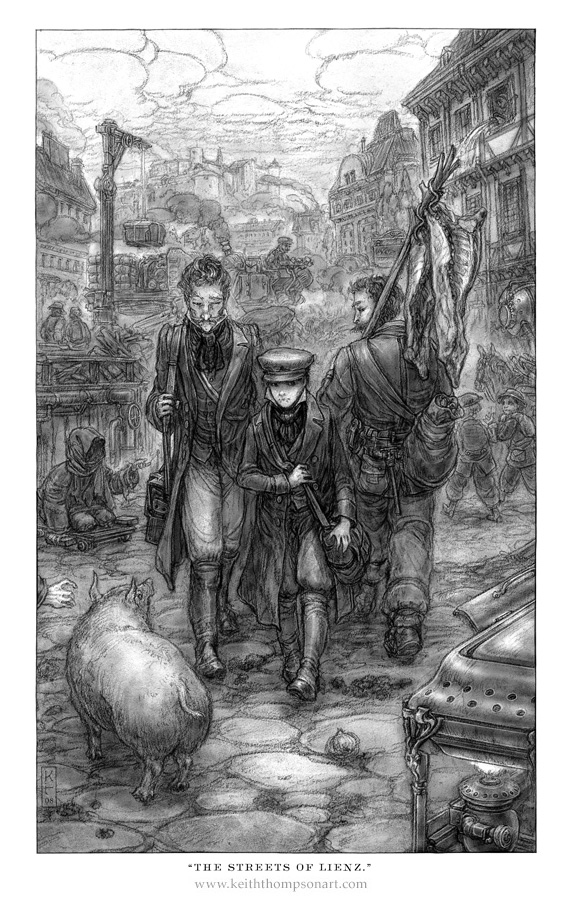

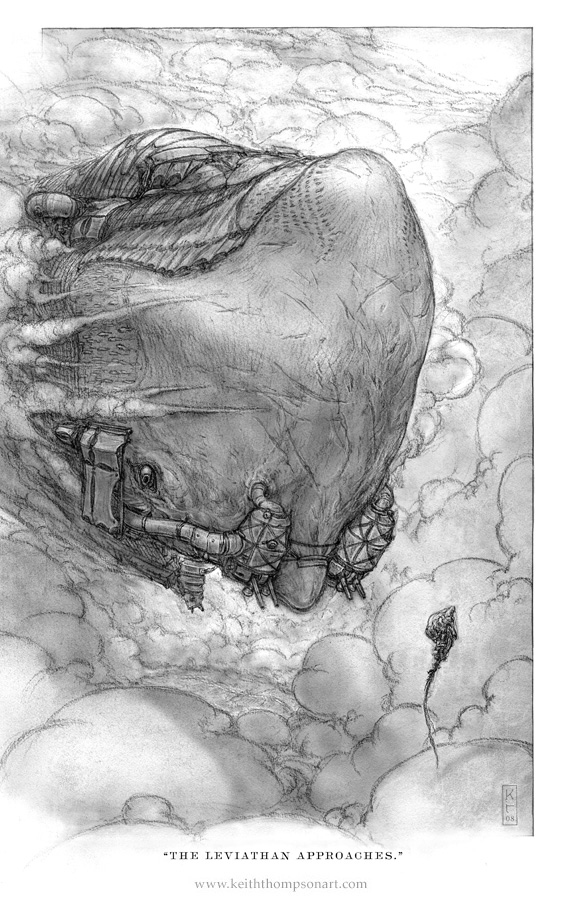

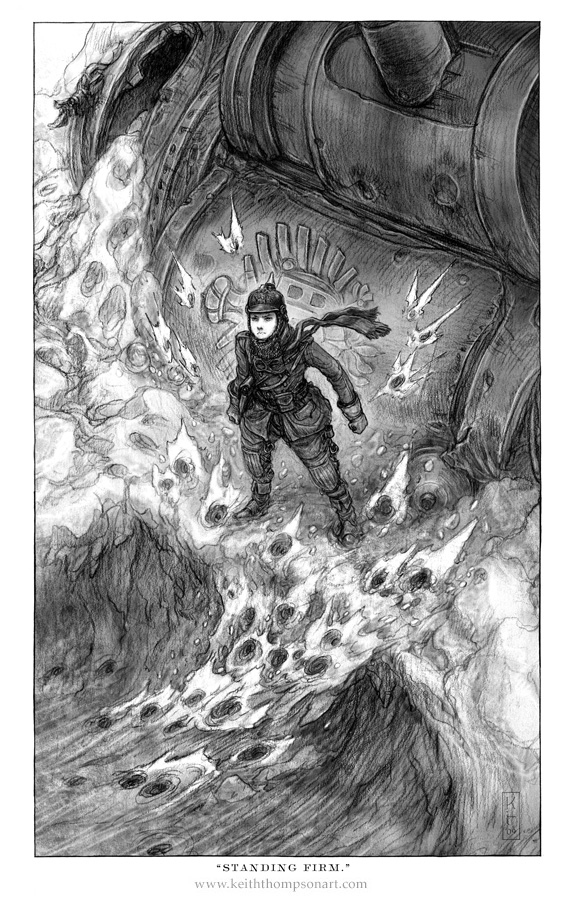

Here is the second half of our “Art of Leviathan” posts. Earlier we talked with Scott Westerfeld about what is was like to be the art director on his own book—the steampunk, young adult novel, Leviathan. Now we have artist Keith Thompson talking about the fifty illustrations that help flush out Scott’s world. Keith did a great job of mixing historical details with fantastical creatures (both mechanical and animal) creating a fun, action packed pace while maintaining the tone of a more formal era.

You did a tremendous amount of drawing in Leviathan, how long did it take you and did it take over all of your working time?

Each book has a year set aside for it, and I go along illustrating it as Scott writes it. It has definitely been the primary focus artistically, though I’ve handled some other things over the course of the year as well. Usually during a batch of research I have plenty of artistic energy to do some work on a movie or game since those jobs are often handled in a comparatively short span of time. It’s nice to have a couple of different worlds I can immerse myself in because I can then switch between them to take advantage of a fresh impression and a new perspective.

Were you a steampunk aficionado before you started on Leviathan?

Were you a steampunk aficionado before you started on Leviathan?

Yes, definitely. Since this is just the way I work creatively, I really only view it as something set in 1914, though. One of the interesting things about steampunk is that it hasn’t formed an expectation of tone in the same way that something like cyberpunk has. If anything, steampunk tends to consistently stress a marriage of form and function, which is really wonderful. This WWI setting also has interesting themes of industrialisation and the steady death of individual craftsmanship,

so in a weird way I can see it being a kind of apocalyptic setup in regards to steampunkery. Steampunk’s last gasp as the world changes. Scott may be taking this alternate past in a different direction though, so we’ll have to see!

What kind of research did you do for the book, either for artistic inspiration or for historical details?

It’s a bit dangerous for me when the setup is as interesting as WWI. I actually had to pull back a bit as my research was taking away time from the art at points and it was making me far too pedantic about my details. That might have been fine for a drier and harder type of alternate past story, but I knew that Leviathan was meant to be a rip-roaring type of adventure and that a fun and fantastical angle to the art was extremely important.

I also wanted to have the historical setting somewhat pliable, as it would be a very bad thing to plunk all these walkers and beasts and things in the middle of history without having ripples spread throughout the setting; changing little things from how a nation’s cavalry uniform looks to how a culture’s architecture has evolved.

I’m learning new interesting things all the time and compiling them into a pretty elaborate collection of research. I’ll be researching right up to the last illustration, and will probably have collected a monumental load of brilliant things I’ll wish I could have incorporated but couldn’t fit in.

I’m learning new interesting things all the time and compiling them into a pretty elaborate collection of research. I’ll be researching right up to the last illustration, and will probably have collected a monumental load of brilliant things I’ll wish I could have incorporated but couldn’t fit in.

Can your describe your working process with Scott?

It has evolved and varied a little as we go along. Usually I get new chapters sent as he writes them and then I fire back with a set of ideas that capture me. Sometimes he’ll have specific scenes he thinks are more key to overarching story and we’ll mix it up a bit based on that, agree on a final list to get going on and then I head off to sketch them all out. Feedback is consistently good to work with, and always framed from a writer’s perspective. Any opinions or concerns are always additive, in that they bring something to the illustration. It’s wonderful to work with someone whose changes and ideas for the art are obviously concerned with the success of the illustration itself and how it works in the book, and not simply one-sided fiddling and rearranging based on individual preference or a stilting focus on the exactness of how a scene was imagined originally.

Can you talk about the advantages, or difficulties, in working directly with the author?

Can you talk about the advantages, or difficulties, in working directly with the author?

In this case it has been nothing but an advantage. Other artists and art directors had regaled me with horror stories of heavy author involvement in illustrations, but that type of risk holds true in every type of creative collaboration. Leviathan’s process has had this wonderfully old-fashioned feel of a writer and artist sitting down together to craft a series of books.

The figures are all well-rendered but never stiff. You’ve done a great job in keeping the action fresh and loose. Did you use a lot of model reference?

I’m glad they come across that way to someone who knows their stuff! There is a type of stiffness in art that I quite like, though, and want to maintain in my own work. It’s somewhat similar to the way that line dominates my approach, and that I trend towards a somewhat orchestrated setup for my subjects.

These days I tend not to use model reference directly at hand. I’ll often set something up to confirm things in my mind, but try not to have it directly viewable upon working. The one exception is if there’s nudity or horses involved, then I always go with model referencing because they’re both such particular subjects. Leviathan had some of the latter, not so much of the former.

You utilize many dramatic points of view, it creates an action-packed cinematic pace to the drawings, especially when viewed all together. Was that something you were conscious of as you started working?

You utilize many dramatic points of view, it creates an action-packed cinematic pace to the drawings, especially when viewed all together. Was that something you were conscious of as you started working?

Yes, but I was extremely conscious to keep any cinematic qualities tightly controlled and subservient to my other artistic focuses. I love the strange distance present in art that predates the major advent of photography; it always had this feel that it was taken down from an imaginative vision, not simply recorded by mechanical equipment. Cinematic angles are certainly much more punchy and initially visually engaging though, so it’s an approach that I’ve tried to incorporate and

mix into the illustrations.

It looks like you had a lot of fun with the machines. Was making characters of inanimate objects something that came natural to you?

It looks like you had a lot of fun with the machines. Was making characters of inanimate objects something that came natural to you?

I love all the technical aspects of any sci-fi or fantasy work. I always try to ensure that the technicals of a world are consistent and well realised. When I bend anything for the sake of creativity I try to make sure the bending is part of a grand reality that then carries throughout the whole existence of the work. If something is possible in this new world because of a stretching of physics then I always try to ensure that this stretching is fully expansive. My primary focus is always to make sure the technology is evocative, and then the hard technicals are built down from it to form a foundation.

What do you do when you are not engrossed in the world of Darwinists and Clankers?

Become engrossed in other created worlds, and in the real one (at arm’s length of course.)

Any plans for what to work on after the Leviathan books?

I’ve been lucky enough to work on a whole mess of different things in my career, and I’ve gotten into the habit of choosing from the new and interesting projects as they come my way.

Irene Gallo is the art director for Tor, Forge, and Starscape Books and Tor.com